ANCIENT RÕUGE

The scenic Rõuge has attracted people’s attention since ancient times. The first traces of human activity here date back to Roman Iron Age (1st to 5th centuries). Around the 5th-6th century, a fortress was established in a narrow strip of land between Rõuge Valley and the narrow Tindioru (aka Ööbikuoru) Valley, and a rather large village arose on the adjacent square, both of which lasted until the 11th century. At present, only building remains and objects hidden in the earth are left. The buildings of the ancient farmstead are located on the northern edge of the former village site.

THE STORY OF RÕUGE EXCAVATIONS

The locals have always remembered the town hill, but archaeologists learned about it only at the turn of the 19th and 20th century, through the words of the young writer Anton Suurkask, who introduced Rõuge Fortress in a letter sent to the ancient history enthusiast Jaan Jung. While digging, he found “coal debris, burnt stones; also bone debris and large teeth…”, as well as “some stone faces and chips” (letter from A. Suurkask to J. Jung). In the early years of the Soviet occupation, when the faculty of human sciences paid a lot of attention to the historical Estonian-Russian relations, it was also decided to study some of the ancient fortresses of South-Eastern Estonia in more detail. The choice fell on Rõuge as a town hill with a relatively small area.

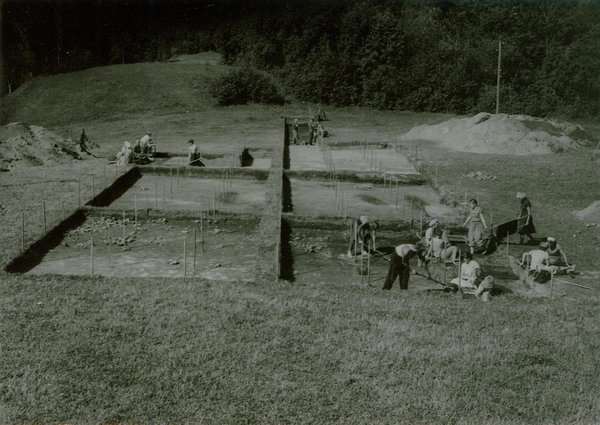

In 1951–1955, the courtyard of Rõuge Fortress was excavated under the direction of archaeologists Harri Moora (1951–1952) and Marta Schmiedehelm (1953–1955). Only most of the eastern mound of the fortress remained untouched at that time. During the research, the cultural layer of the ancient village was discovered in the field next to the town hill, which was then included in the excavation plans. About a quarter to a third of a settlement of about 0.75 hectares was excavated during fieldwork led by Marta Schmiedehelm in 1956-1959.

Due to the abundant data and findings collected during fieldwork in the 1950s, Rõuge became one of the model examples of Estonian Viking-era fortress settlements in archaeology. To this day, it is the only Estonian fortress with a completely researched courtyard.

In order to find out the age of the fire layers in the eastern wall of the fortress, the University of Tartu organised small-scale excavations on the fortress wall (approx. 5 m2) and at the bottom of the moat in 2008, led by Anti Lillaku and Heiki Valgu. It turned out that most of the charred wood found in the wall came from the 7th-9th centuries. Viire Kobrusepp has carried out minor archaeological research in the area of the Iron Age village, in connection with the construction of an ancient farmstead and a swing on the edge of Rõuge Valley.

Most of the ancient artefacts found during the excavations are kept in the archaeological collection of Tallinn University (fortress finds as AI 4040, settlement finds as AI 4100), some of which have been deposited to Estonian National Museum’s permanent exhibition “Meetings”. The finds from the excavations of the fortress in 2008 are located in the archaeological collection of the University of Tartu (UT 1696).

Archaeological excavations on Rõuge hillfort in the 1950s. Photo from the archives of the Archaeological Research Collection, Tallinn University.

Excavations at the village site in the 1950s. In the background, the hillfort. Photo from the archives of the Archaeological Research Collection, Tallinn University.

Archaeological excavations on the fortress wall in 2008. Photo: Anti Lillak.

REMAINS OF BUILDINGS

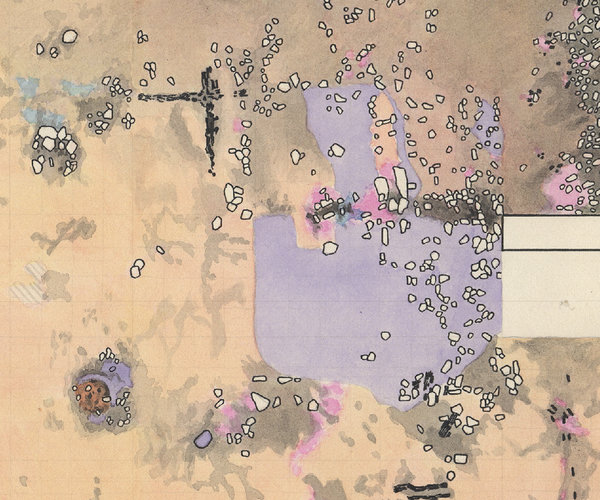

In ancient times, Rõuge may have been a densely built-up settlement with several hundred inhabitants. Few buildings more than a thousand years old have survived to this day. During the excavations of the castle, five or six thin clay floors of indeterminate shape were found, on the basis of which the sizes of the buildings have been assumed. The smaller ones were limited to 2.5 × 3 meters, while the larger ones reached 5 × 6 meters. They were probably mainly cross-beam huts with a hot stone furnace made of round boulders or a clay-top stove in one corner. From the walls of the buildings, only the charred remains of the lower log layer have survived, if not less, and a dog neck joint can rarely be observed.

The fortifications on the ramparts were also carved from logs, some of which may have been used as dwellings. Remains of a supposed smithy have been found on the town hill, where, in addition to iron processing, pewter, bronze or silver jewellery was probably cast.

During the warm season, food could be prepared in cone-shaped summer kitchens made of boards leaning on each other, of which only stone-laid fireplaces have survived. There were definitely several auxiliary buildings in the village - barns, stables, saunas. Numerous pits have been found in the fortress and the village, which were apparently used for food storage, waste depositing, coal burning, etc.

Detail of an excavation drawing of the hillfort. Purple depicts the clay floor of a building, to the left of which there are two charred base beams connected by a dogneck joint. Here and there are hearths laid of stones. Drawing from the archives of the Archaeological Research Collection, Tallinn University.

Two stove types from the settlement. On the left, the bottom of a hot stone stove, laid of stones; on the right, the remains of the clay-top oven. Photos from the archives of the Archaeological Research Collection, Tallinn University.

The charred log fragments, rather well-preserved in some places, are laying in the moat and come from the fortifications of the hillfort. Photo: Anti Lillak.

FIELD CULTIVATION

The Viking-era man got his main food from the field. Slash-and-burn cultivation was common, in which trees and bushes were cut down on the plot and set on fire. The land fertilised with ash yielded a very good grain harvest for a few years, but then it had to be abandoned and a new land plot had to be cleared in the same way. One sickle fragment and one scythe fragment have been found in the village. Most of the tools were made of wood and have not survived inside the earth.

What crops were grown in that field? Barley, wheat and rye pollen have been detected in the bottom mud layers deposited in the lakes of Rõuge during the Viking Age, but calculations show that there were apparently quite few arable lands around Rõuge at that time. A whole pot of barley grains has been found in the castle, and sometimes fragments of grains (eg rye) left in the clay during pottery making have been preserved on ceramic fragments.

The trace of a suspected rye grain on the surface of pottery. Photo: Tarvi Toome.

FOOD AND DISHES

We do not have much information about the diet of Ancient Rõuge. The most common foods were various cereals – made into bread and porridge. Beer was also brewed from barley. The flour was ground with round flour stones that could fit in the hand. The meat of both domestic animals (including probably even horses) and wild animals such as elk and beavers was eaten. As the hooks and the fish bones in the cultural layer show, the fish also had a firm place on the table. Certainly the people picked berries, mushrooms and nuts from the forest and collected honey from wild bees. The honey was also used to make a sweet, lightly fermented drink called mead.

The pottery needed in the household was apparently made by each family on their own. Viking dishes are generally divided into two groups. The so-called coarse ceramic dishes are quite large and have a very simple finish. They were probably used to store food. Sometimes a series of small holes are pierced at the top of such pots, which may have been intended to ventilate a pot covered with a lid. However, pots and pans decorated with a carefully smoothed surface and sometimes with patterns - so-called fine ceramics - were used to serve food, including when hosting guests.

A grinding stone. One side of it has become shiny smooth due to long-term friction. Photo: Viire Kobrusepp.

A coarse ceramic pot with a row of small holes under its edge. Photo: Viire Kobrusepp.

The fine ceramic bowl was apparently intended for serving food. Photo: Viire Kobrusepp.

CLOTHING AND JEWELLERY

The clothes themselves have not survived in the cultural layer of Rõuge, so we know very little about them. Yarn spinning was probably the daily work of women, because spinners attached to spindles are very common among ancient finds. Fabric weights, needles and awls also testify to the manufacture of clothing. The yarn was spun and the fabric was woven from flax and wool; animal skins were used to make winter clothes, shoes, belts and maybe also aprons. Fur was certainly worn with more beautiful clothes.

Jewellery was worn by both men and women. Different areas of the body have been emphasised, especially with various necklaces and chest jewellery. Small fragments of the necklaces have survived, often trapezoidal bronze pendants hung on them. Bead necklaces were popular; in addition to more expensive glass beads, homemade clay beads were also worn. The women’s jewellery set included long hanging chains that were attached to the clothes with decorative pins above the shoulders. Animal teeth were worn around the neck or on a jewellery necklace. It may have been due to the belief that through the tooth, the wearer gained the power of the animal. Temple rings were sometimes attached to women’s headscarves. Beautifully ornamented open-ended bracelets were worn around the hands, and bronze wire spiral rings on the fingers.

The horseshoe brooches used to fasten the garments were mostly made of iron, and because of their simple mode of operation, they were not so much a jewel as a practical commodity.

Clay, stone and bone spindles weights from the town hill. The fragment of a large clay disc in the lower right corner may be a fabric weight. Photo: Viire Kobrusepp.

Bone handles were made for iron awls (on the left side). On the right there are bone awls. In the upper left corner there is a curved knife that could have been used in leatherworks like awls. Photo: Viire Kobrusepp.

Jewellery pins with a triangular head on the left, a bracelet on the top right, a piece of a necklace in the middle, and glass beads on the bottom. Photo: Viire Kobrusepp.

Bells and a spiral ring in the top row. The trapezoidal pendants in the bottom row were probably attached to a necklace. Photo: Viire Kobrusepp.

Iron horseshoe brooch with a broken needle. Photo: Viire Kobrusepp.

TRADE

Although the people of Rõuge procured and made most of what they needed for life, they had close trade relations with countries near and far. Contacts with southern neighbours are evidenced by several jewellery items that were fashionable both in Southern Estonia and in Latvia – brooches, necklaces and bracelets. The stone needed for jewellery moulds has also been brought from Southern Lithuania or Central Europe. And the blue and yellow glass beads were made both on the Scandinavian Peninsula and in Central Asia.

Probably the most exotic archaeological finds in Rõuge are silver coins from Arab countries, of which ten have been found in the fortress and six or seven in the settlement. Brisk north-south trade followed the great rivers of Eastern Europe during the Viking Age, in the 9th–10th century. The durable and densely haired Nordic fur was appreciated in the East, for which the people there were willing to pay a very good price. Thus, Arabic silver coins reached the north, including our land. When the silver deposits of the East were exhausted, trade relations in that direction also stagnated in the 11th century, gradually being replaced by business ties with Western Europe. Four German coins have been found in Rõuge. They probably arrived here shortly before the fortress settlement died out.

Four Arabic silver coins were hidden in the ground in the castle, together with a small bird statue and an unfinished comb pendant. Photo: Anti Lillak.

SOCIAL ORGANISATION

Rõuge is one of the many Viking-era settlements in Northern Europe, where a large village and a small fortress were located side by side. Yet, the inhabitants of the fortress were clearly separated from the village by a rampart and a moat, which indicates their special, preferred position in the society. Apparently the chief (who may have been called the king) and his immediate staff resided in the fort, ruling over the villagers. The king decided on the most important things in the community; he could have been responsible for tax collection, local trials, defending the fortress and organising military expeditions. The chief also probably had the power to organise trade relations, while also benefiting the most from them.

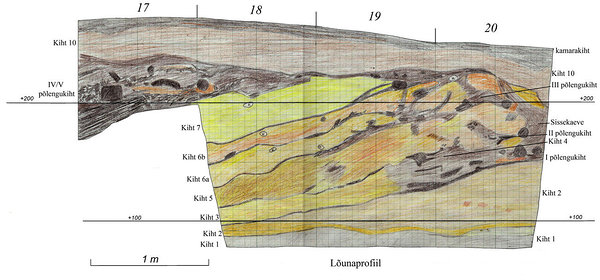

Strength was needed to secure the king’s power. The staff of the chief living in the castle apparently also included an armed military unit. The spearheads of iron found in the cultural layer of the town hill may have belonged to these warriors. The spear was a versatile weapon used in both combat and hunting. Several successive layers of burnt logs in the end wall of the town hill point to the times of hostility in Rõuge. Although it seems that the fortress has been burned down at least three times in a short period of time, sometime between the 7th and the 9th century, the inhabitants of Rõuge have always had the strength to rebuild their defences every time.

In total, the fortress has been destroyed five times during its lifetime of more than half a thousand years (the 5th / 6th-11th centuries). At the same time, a fire accident cannot be ruled out for at least some of the fires, especially considering that many of the works done in Rõuge - smelting iron, blacksmithing, burning earthenware, etc. - were quite a fire risk and the wooden buildings were very close to each other.

Spear ends, which may have belonged to the military staff of the fortress chief. Photo: Viire Kobrusepp.

Several layers of material from fires can be seen in the castle wall. Detail of the 2008 excavation drawing.

LIVESTOCK AND HUNTING IN VIKING-ERA RÕUGE

Numerous bones and teeth provide evidence of the importance of animals in the daily lives of the ancient inhabitants of Rõuge. Most of the waste comes from the kitchens and dining tables, but there is also ample evidence of bone and horn processing, the production of (fur) hides and the wearing of animal pendants.

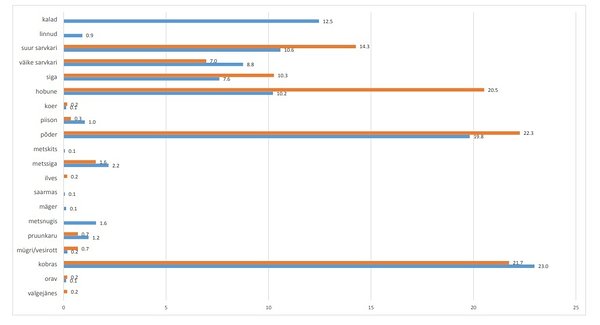

Most of the animal bones excavated by archaeologists from Viking-era fortresses and settlements usually belong to domestic animals such as cattle, sheep, goats, pigs and chickens, and indicate the importance of livestock farming to the people of that time. Livestock farming was also important in Rõuge, but some peculiarities stand out here, making Rõuge one of the most remarkable archaeological site compared to other fortresses / settlements of that time. Namely, Rõuge was a place where a lot of big game and fur animals were hunted and the settlement was part of an important trade network.

Viking-era domestic animals looked slightly different from modern new breeds. They had a smaller growth and rather resembled current country breeds such as the Estonian horse or the Kihnu land sheep. For example, the height of cattle at the withers was only about a meter, while the wither height of horses was only 130 cm. However, this did not prevent the ox from being used as a working and draft animal or the horses for riding. Pigs were raised primarily for meat production and sheep for wool production. Eventually, however, most animals became meat and other essential animal products such as tendons, skin, fat and hair. The numerous horse bones found in Rõuge have given reason to believe that horsemeat was also the usual meat part of the meals in the community there. The dog was a necessary helper on hunting trips, but also just a valued companion.

Very little is known about animal husbandry and living conditions at that time. One can only assume that the animals had certain shelters or stables, especially for winter survival. During severe weather, animals could also be kept in the same building - keeping both animals and people warm. In Rõuge experimental ancient farmstead, however, we have solved this problem with a separate construction - a barn made of cross logs, which would nicely house the whole supposed family of animals - cattle, horses, some sheep, a couple of pigs and a herd of chickens.

One of the indicators of the economic success of Rõuge’s population was definitely the hunting of big game and the fur trade. The bones and teeth of elk, beavers, wild boar, bears, grouse, bison, squirrels, badgers, hares, otters, lynxes and wild goats make up more than half of the few thousand bone finds. Even some bones of hedgehogs and water rats have been found here, but it must always be borne in mind that the bones of such small mammals may have ended up in the heritage site accidentally, by natural causes (for example, if the animal found its natural end there).

Among Rõuge’s game finds, beaver and elk deserve special attention. These two species have been hunted the most, with the trade in beaver fur and castoreum being even more important than beaver meat in the East. In the South, dense fur from the North was valued, but castoreum was once considered an effective potency medicine. The importance of the beaver is also indicated by the pendants made of beaver’s heel bones and found in Rõuge.

The bison bones are also extremely interesting, as they have been found in only a few sites in Estonia (from Viking-era Viljandi besides Rõuge), but they prove that this magnificent large mammal spread so far north of Southern Europe during that period that it found a suitable habitat in Southern Estonia. Hunting these magnificent animals was certainly a difficult and dangerous undertaking for the people of that time.

In addition to hunting, fishing was also taken up in Rõuge. The main prey fish could be pike, bream and other freshwater species. Bird hunting was also likely to take place, but little evidence has been investigated about that.

A thousand years ago, animals certainly had not only economic value. Various mammals, birds and even fish had a place in people’s beliefs and in the worldview. This is evidenced by animal figures (such as waterfowl with a worm body depicted on comb pendants made of horn) or by horses, dogs and carcasses accompanying the dead. In Rõuge, a number of bone and tooth pendants express the relationship between a person and an animal. The aforementioned beaver heel pendants have been directly linked to the trade in fur and castoreum and to the revenue generated therefrom. However, it cannot be ruled out that the heel bones were hung on a belt or a necklace to improve hunting luck. The people of Rõuge have also adorned themselves with bear, wolf, marten and wild and domestic pig fangs. The only pendant made from a domestic animal is a horse’s tooth, which refers to the horse’s value as a working and riding animal.

In 1965, Kalju Paaver identified the animal bones of Rõuge town hill (blue) and settlement (orange). The bar graph presented shows all the analysed animal species or their groups in proportion (percentage). Note the remarkably long list of wild animals. Also note that incomplete material does not necessarily mean that the animal was not hunted or consumed. For example, the absence of fish in the settlement material refers to the excavation methodology (no fish bones were harvested), not to the fact that the ancient villagers consumed no fish at all.

Beaver skin.

Bison toe bones found in Late Iron Age Viljandi. The left toe bone has a hole likely to be man-made, while the right bone fragment has clear longitudinal incisions. Photo: E. Rannamäe.

Read more about faunal remains (in Estonian):

Leimus, Ivar ja Kiudsoo, Mauri (2004) Koprad ja hõbe. Tuna 4, 31−47.

Lõugas, Lembi ja Kihno, Kersti (1999) Eesti metsades kõndisid piisonid. Horisont 5, 52−56.

Maldre, Liina ja Lõugas, Lembi (2001) Hobune Eestis muinas- ja keskajal. Hanna Tamsalu (toim.) Meie hobune: arvamusi ja tähelepanekuid eesti hobusest ja tema kasutamisest. Tallinn, Eesti Hobuse Kaitse Ühing, 28−34.

Lõugas, Lembi (2002) Karvasest mammutist ameerika naaritsani ehk Eesti loomastiku arengulugu. Eesti Loodus 9, 16−13.

Lõugas, Lembi (2003) Vanad kondid ei kolleta asjatult. Eesti Loodus 10, 14−17.

Jonuks, Tõnno ja Rannamäe, Eve (2015) Loomad ehteks – hammas- ja luuripatsid Eestis kiviajast keskajani. Tutulus: Eesti arheoloogia aastakiri 4, 18−20.

Rannamäe, Eve (2013) Vanad loomaluud maapõues. Tutulus: Eesti arheoloogia aastakiri 2, 14−17.