Barcode: 0726754943843

Playing “The Vikings of the Eastern Road” is fun but also very educational, as it helps better to understand the events of a world separated from us by over a thousand years.

In this game you will travel back in time to the Viking Age - to a time when brave adventurers sailed the seas and rivers to many distant lands to bring home treasures gained through trade or conquest. As a player, you are an intrepid sailor who, defying many difficulties, attempts to bring home as much

Arabic silver as possible. At the beginning of the game, you will get Viking ships loaded with Nordic beaver skins. You will then head to the east and to the far south to trade them in the rich Byzantine and Arab cities. There you can exchange beaver skins for silver in the shape of Arabic silver coins, which you can subsequently use to acquire cities, ships and followers.

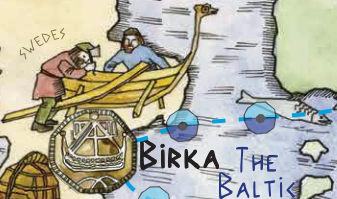

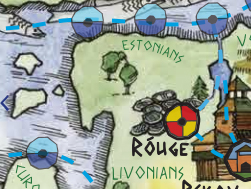

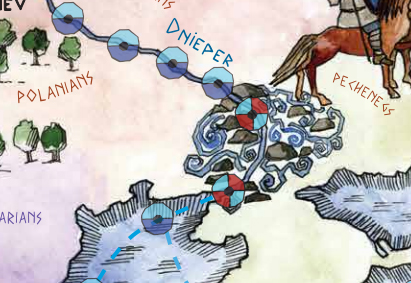

The game board, the playing cards and the game box are all illustrated with original drawings by artist Epp Margna. All the illustrations on the board are related to the Viking era, including themes from mythology, culture, shipping, nature and economic geography. The texts on the 64 playing cards also give small insights into the Viking Age.

The game is made of natural materials and is as historically factual as possible. Birch, cherry, walnut and ebony trees have been used to make the wooden buttons, 50 melchior coins are reduced copies of dirhems found in the Viking Age settlement at Rõuge. The only plastic playing pieces are the dice, that were created to look like Viking era bone dice.

The Vikings of the Eastern Road - historical background

The Vikings were mainly Scandinavian sailors, soldiers, explorers and merchants. Their expeditions extended far to the north and west, as well as to the east. To the east went mainly the people of Svealand and Götaland, who lived in the areas of modern Sweden. Birka became the main trade centre. In the eastern lands, the Vikings were also called Varangians. Vikings were also known as the Rus, derived from the name of the Roslagen region of eastern Sweden. Later, the name was transferred to the East Slavic tribes, where the Vikings stayed put.

The Scandinavian Vikings had very good ships of their time, which were light, fast and suitable for navigating rivers. They were more like big boats. The ancient ships sailing in the Baltic Sea got a sail somewhere between the 6th and the 8th century. The remains of the oldest sailing ship sailing in the Baltic Sea have been found in Salme, Saaremaa (mid-8th century), where a large number (41) of soldiers who probably came from Sweden are also buried. In addition to human bones, various weapons, game pieces and dice were also found there.

The first trips to the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea or the East Road (Austrvegr) were made already around the year 600. On the way to the east, the land of Estonian settlements was crossed, as evidenced by the fact that many Arab dirhems have been found in the territories of modern Estonia, being second by amounts only to the finds in Sweden. Arab dirhems were the coins used in the Arab lands; they were made of silver and brought back to the North by the Vikings, both in the form of coins and in the form of cast silver bars shaped like bracelets.

One of the best-studied fortress settlements that actively traded with Vikings from Scandinavia was Rõuge Fortress Settlement. It is also home to some of the oldest northern European dirhems, dating from the Abbasids (a dynasty located in what is now Iran) and minted in 808/809. Numerous wild animal bones have also been found here, especially of beavers. In the Arab world, beaver skins were a highly valued commodity because of their durability.

Through the areas controlled by the Estonians, the Vikings reached the rivers of present-day Northwest Russia and through them the rivers Volga and Dnieper, via which they reached the riches of Islamic countries and the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) empire. The journey was long and it took about 40 weeks to get from Birka to the destination. On the board game map, the distance between spots is approximately equal to one week's journey. Some rivers had more rapids and these waterways were used less frequently. An example of such a river was the Daugava (Väina). It was often necessary to stay in a populated area for a while to wait for favourable weather conditions. Moving along the Dnieper River towards the Black Sea, the Vikings reached dangerous rapids. One might have easily lost their cargo or ship in that area. There were also dangers present when pulling the ships by land. This area was under the control of hostile tribes, Hungarians and Pechenegs. Because of that, they waited in Kiev for favourable weather conditions in order to access the Black Sea as safely as possible.

On their way, the Vikings built fortified bases. In the 8th-9th century, the Vikings established a Russian country joining different tribes (Baltic, Slavic, Finno-Ugric and Scandinavian) and having its centre in Ladoga (in Aldeigjuborg). According to Russian chronicles, in 859 the people of Novgorod raised against the Vikings but after three years of war, the country was called to rule by the Viking chief Rjurik, who united the tribes living in north-western Russia under a single leadership. He is considered the founder of the Russian Principality, with its centre in Novgorod. The next Varangian ruler, Oleg, continued with conquests, and in 882 he conquered Smolensk and the rich trading city of Kiev. He annexed these territories to the Principality of Novgorod and formed the Kievan-Russian state, which united the North and South Slavs. Important settlements on the East Road were Ladoga, Novgorod and Pskov, Polatsk, Gnezdovo, Timeryovo and Kiev, which were enriched by trade between the Nordic countries and the Byzantine empire and between Abbasid caliphates and the Samaritan state. In the board game, the player can also buy or conquer a city to deposit his or her accumulated wealth, earn money by collecting duties from other players and, if desired, expand his or her fleet.

On the East Road, the Vikings faced various dangers: hostile tribes, natural barriers and other obstacles.

The trade route to the Caspian Sea ran along the Volga River. This river was surrounded on the north by mainly Finno-Ugric tribes. After the break-up of Greater Bulgaria, some Bulgarians moved to the middle of the Volga River and mingled with the Finno-Ugric tribes there. They founded the Volga-Bulgarian state, with Bulgar as its capital. In 922, Islam became the state religion there, and after that the Caspian Sea was no longer accessible along the Volga. Silver from Central Asia was thereafter traded with the Volga Bulgarians, who took great profits from it.

The Vikings also used another road to Central Asia, which crossed a narrow land strip controlled by the Khazars, located at the point where the Don and Volga rivers were closest to each other. It was probably possible to use the help of local tribes to transfer ships across it.

Constantinople and other Byzantine cities were the main export market for Varangian traders, where slaves were supplied in addition to traditional Nordic goods. Expensive fabrics, wines and luxury goods were imported from Byzantium, in turn. Rich Byzantium was not only a trading partner, but also the object of attacks that, if successful, promised rich loot. In 866 the first rulers of Kiev, Dir and Askold, plundered Constantinople. According to lore, the fleet consisted of almost 200 vessels. Sudden storm winds sank most of the Rus ships and stopped the destruction. Only a few of them managed to return. From this event, the chronicler Nestor began to take into account the history of ancient Russia. The next conquest of the Rus to Constantinople was organised by the Grand Duke Oleg of Kiev-Russia in 907. According to the chronicle, Oleg had assembled a huge army of 80,000 men from the Varangian, Slavs and Finno-Ugric men, and had sent them on 2,000 ships. The attack on Constantinople came suddenly to the Byzantines. To escape the critical situation, they offered gold and other benefits to the conquerors. In the peace treaty between the two countries, Rus merchants gained privileges and also the documented obligation to provide military assistance to Byzantium. Over time, attempts were made to withdraw from various agreements, which led to tensions between the two countries. In 941, Prince Igor attacked Constantinople. This time the Byzantines were better prepared for the battle with the Rus, and thanks to the use of “Greek fire”, most of the Varangian fleet was destroyed. Greek fire was an ignition mixture that did not go out even in water. Despite the pitiful defeat, Prince Igor attacked Constantinople again in 944, this time in union with the Pechenegs. Relations between Kiev-Russia and Byzantium did not improve until after the marriage of Grand Duke Vladimir and Sister Anna of Emperor Basil II in 988 and the conversion of the Rus to Christianity. In the game, you also have the opportunity to form alliances with other players who have a daughter or son card, in opposite gender to your card.

In 989 the famous emperor Basil II’s troops consisted of 6,000 Viking mercenaries who stood out for their courage. As a token of gratitude, the emperor later formed a Varangian bodyguard in Constantinople. In the board game, the player can also go to Constantinople to earn money in the absence of other earning opportunities.

See video of "The Vikings of the Eastern Road" here:

(for fullscreen view, open the video in YouTube)

Extra reading in English:

- Brink, S. with Price, N. (eds) (2008). The Viking World, Routledge: London and New York, 2008.

- Graham-Campbell, J. (2001), The Viking World, London, 2001.

- Mägi, Marika (2015). "Chapter 4. Bound for the Eastern Baltic: Trade and Centres AD 800–1200". - Barrett, James H.; Gibbon, Sarah Jane (eds.). Maritime Societies of the Viking and Medieval World. Maney Publishing, pp. 41–46.

- Tamla, Ülle; Kiudsoo, Mauri (2009). Ancient Hoards of Estonia. Tallinn.

- Tvauri, Andres (2012). The migration period, pre-viking age, and viking age in Estonia.

Extra reading in Estonian:

- Lang, Valter (2003). Baltimaade metalliaeg. Õppematerjale. Tartu.

- Kiudsoo, Mauri (2016). Viikingiaja aarded Eestist. Idateest, rauast ja hõbedast. Tallinn.

- Kiudsoo, Mauri (2019). Eesti muinasaarded. Kaubateed ja -kontaktid. Tallinn.

- Kobrusepp, Viire; Lillak, Anti (2014). Rõuge – muinasajast muinasmajani. Tartu.

- Leimus, Ivar; Kiudsoo, Mauri (2004). Koprad ja hõbe. Tuna. Ajalookultuuri ajakiri, 4, 31−47.

- Roesdahl, Else (2007). Viikingite maailm.

- Tamla, Ülle; Kiudsoo, Mauri (2005). Eesti muistsed aarded. Tallinn.

- Tvauri, Andres (2012). Rahvasterännuaeg, eelviikingiaeg ja viikingiaeg Eestis. Tartu.